In a cozy house, just a few blocks from downtown Charlottesville, Darrell Rose—musician and painter, and all-around intellectual—and I are sitting on a sofa talking about how hard it is to talk about art. Rose is telling me that he can’t explain most of his work, but somehow, we manage to start talking about his process: “I used to question it more,” he tells me, “but it just is.”

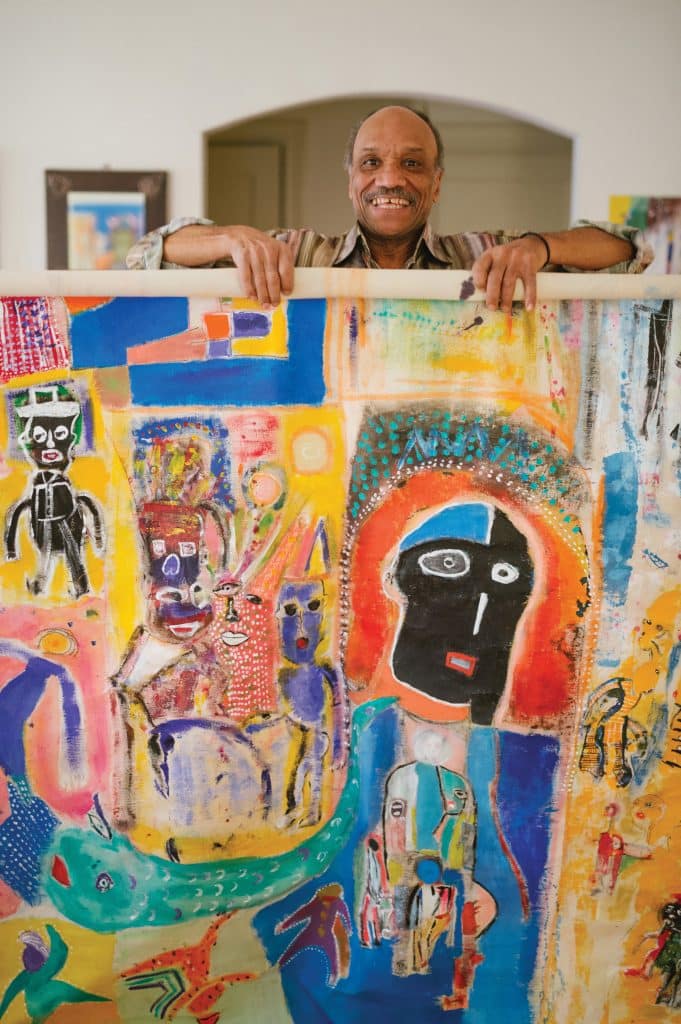

The house is full of Rose’s artwork, with three paintings hanging over the fireplace alone, and Rose brings in more from other rooms as we talk. Despite his disclaimer that he doesn’t know how to talk about his art, he has the story, the analysis and the way in which each work fits in with the larger dialogue of art history.

His painting “Backstage” starts a discussion on the influence of Cubism and collage on the work, as well as that of his New Orleans heritage and performances. Other paintings in Rose’s prolific collection show influences across art history, from Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism to the Fauvists; and Rose discusses how De Kooning, Miro and Picasso have inspired his acrylic paintings for more than 25 years.

Rose’s Journey to Painting

Best known for his fascinating career as a drummer, especially for his time with Reggae band “The Wailers,” and for teaching percussion to generations of eager students, Rose deserves no less acclaim as a visual artist. He began painting in 1992 when one of his percussion students, Charlottesville’s McGuffey Art Center member Gloria Mitchell had to stop studying with him after an accident that injured her wrist. She invited Rose into her studio, gave him a canvas and various paints, and told him to think about his music. Rose describes how he was “intimidated” by the process, but he returned, studying with Mitchell every week for several years. His first show at the original Mudhouse Coffee in downtown Charlottesville propelled his art career forward to a membership at McGuffey and exhibitions at numerous other Charlottesville locales, including BozArts gallery and Second Street Gallery (where he has also served on the board).

Touring the house, where the number of drums exceeds the amount of furniture, and the amount of paintings exceeds the number of drums, I can see the intensity and focus that Rose brings to his art forms. The physical intensity of performing and painting, both of which require Rose to lose himself in the process, takes a toll. Rose actually stopped painting for two years when he found it too demanding to balance with his music. He often forgets to remember to eat and drink. Like the rest of us, Rose is looking for balance between the physical and the mental, and between the music and the painting. He is quick to share his knowledge of how painting nurtures his performances and his availability to give, but instead of seven- or eight-hour painting sessions, he tries to now paint in two-hour segments.

He approaches his canvasses with what he describes as “total respect and a lack of ego” and lets the painting speak to him, telling him when they are done.

Aside from the years he studied with Mitchell, Rose is an entirely self-taught artist. His extensive travels and his willingness to seek out museums and galleries keep his work relevant and serious. Every month from 2007 to 2010, Rose went to the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., a modern art museum in DuPont Circle. Listening to him describe the experience of sitting in the small gallery devoted to paintings by Mark Rothko and looking out the door to see the paintings by Paul Klee, it’s clear that Rose is painting to be in touch with the same interplay of color, shape, movement and emotion as his artistic mentors.

What Inspires Rose’s Artwork

Painting is also a way for Rose to honor and communicate with his heritage. Adrienne Sordelet, his deceased mother, is present, in some form, in just about every painting he creates. In addition, many of his works have an element of self-portraiture in them. Rose also draws from both his North African and French heritages, as well as his New Orleans upbringing, all filtered through a lifetime of extensive travels.

Unlike a musical performance, a finite end to the painting often eludes Rose. While some of his paintings can take only an hour, others pull him back again and again, and can span years until he feels they are finished.

He approaches his canvasses with what he describes as “total respect and a lack of ego” and lets the paintings speak to him, telling him when they are done. He is comfortable sitting with blank spaces, waiting for the forms to reveal themselves, and for the right input to come to him and then through him onto his canvas.

As we continue our conversation, I find myself theorizing that Rose embodies the collective unconscious articulated by Carl Jung.

Jung’s idea of archetypes and symbols that we all can access, even if we don’t acknowledge our understanding of them, seems to seep through Rose’s work. At one point, Rose shows me an unfinished painting with a face and various linear elements. Looking at it, I’m reminded of a painting by Odilon Redon, “The Cyclops.” I pull it up on my phone to show Rose, and as I stare at the 1898 painting, which resides in Otterlo, Netherlands, I am taken aback by its conversation with Rose’s own work.

Other works by Rose, too, seem to show evidence of his influences by famous and well respected artists. It is his desire to always be a student, never a teacher of art.

Though he’s had the title of “Artist-in-Residence” at Mountaintop Montessori in Charlottesville since the mid 1990s, he’s also offered art classes throughout the community as well as music classes at the Field School in Crozet, Virginia, Rose says he can’t teach art. “I respect the art form too much to do it,” he says. Certainly, it would be hard to provide the studio atmosphere Rose enjoys, involving candles and music, in a classroom setting. But, what Rose has done sounds like an ideal art class to me: providing the materials, the atmosphere and gentle questioning or nudging to encourage students to get in touch with their own creative forces, to determine when a painting is finished and what a work means.

The effort required to constantly operate at such a level of creative consciousness is high. “I’d cherish a day without music and art,” Rose says. But after a brief minute contemplating this, Rose laughed, dissolving his statement, brought out another canvas and continued with our talk. ~

This article appears in Book 6 of Wine & Country Life. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here. You can find some of his artwork for purchase at our Wine & Country Shop in Ivy near Charlottesville.

A resident of Albemarle County, CATHERINE MALONE has written for Wine & Country since its inception.