In the wee hours of a colder-than-normal morning, that time of day when the sky begins to brighten but the sun is still just below the horizon, farmers of all types find themselves ready to begin their daily tasks. On the Rappahannock River less than ten miles from the Chesapeake Bay sits a tiny workshop on a small wooden dock. From here, you can see about half a dozen oyster boats and stacks of oyster cages.

I love oysters. I remember sharing some of my first oysters with my father, standing at the District Wharf in Washington, DC, as a teenager. And I remember eating them fresh off of the boat with saltine crackers and cocktail sauce, with the sound of Saturday morning shoppers hustling and bustling around and the smell of the Tidal Basin filling my nose.

Even now, sitting at a seafood restaurant in Charlottesville, hearing the clinking of plates and glasses, the din of laughter and conversation, and the crisp snap of the shell as the lid is separated from the base just takes me back to those days of my youth.

The Flavor of Virginia Oysters

Oysters have one of those tastes that is easy enough to describe. At its most elemental, an oyster’s flavor is briny. The French poet Léon-Paul Fargue once wrote that eating an oyster is “like kissing the ocean on the lips.”

Each oyster is different, though, taking on the flavors of the waters in which they grow. Some have the deep salt flavor of the ocean, while others carry the sweet, buttery minerality of inland waters. Some have a firm texture, while others are juicy and explode in your mouth.

As Ean Reed and Chris Pitts, two of the farmers at the Rappahannock River site, pulled into the parking lot that morning, they quietly went straight to their tasks. As the sun began to rise, we all headed out onto the water, trolling along the marked lines, periodically stopping to lift cages teeming with oysters onto the boat so that we could return them to the dock for sorting. These cages, a relatively new development in the collection of oysters in Virginia, are becoming a standard practice for farmed oysters around the world.

Oyster Festivals in Virginia

Across the nation, we are seeing a resurgence of oyster sales and of the local oyster bar. In Charlottesville, raw oyster bars, such as Public Fish & Oyster, serve Rappahannock oysters. In addition, annual Virginia oyster festivals featuring their oysters are held at Cardinal Point Winery, Early Mountain Vineyards and DuCard Vineyards, and dozens of other wineries. Many restaurants are also serving sustainable oysters from Rappahannock Oyster Co.

So, needless to say, Virginia Wine Country loves their oysters. With the success of the farm-to-table movement in the state over the past decade, it’s no surprise that residents are becoming more and more interested in where their shellfish originate. In the same way that we have started to turn to local farms for our land-based foods more and more, the demand for oysters has been met not by large companies but by small farms often with just a few employees.

The History of the Virginia Oyster Industry

On that small dock in Topping, Virginia sits the home of Rappahannock Oyster Company. It’s a business that not only produces some of the best oysters I’ve ever tasted but also is on the forefront of saving the nearly endangered Chesapeake Bay oyster, reviving Virginia’s oyster industry, and helping to clean and revitalize the Chesapeake Bay.

With Virginia being a coastal state, oysters have been a part of Virginia’s food culture since its earliest days. Native Americans dined on them before European settlers arrived on the shores. Governor George Percy, in his days of exploration with John Smith, wrote in his 1607 journal that “oysters…lay on the ground as thick as stones.” The streets of Colonial Williamsburg are paved with crushed oyster shells and the mortar for the brick buildings of the day came from oyster shells as well. Even Thomas Jefferson couldn’t get enough of them. According to author James Gabler, Jefferson once polished off 50 oysters in a single sitting.

Founding of the Rappahannock Oyster Company

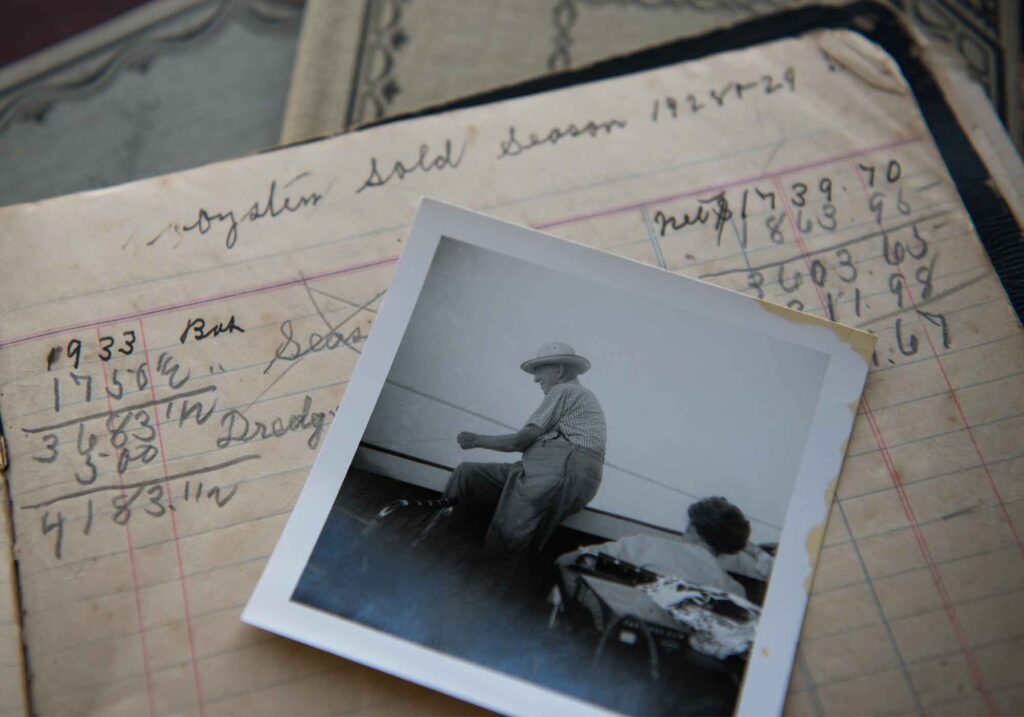

By the late 1800s, Virginia was supplying nearly half of the world’s demand for oysters, upwards of 20 million bushels of oysters each year. It was around this time that James Croxton laid claim to two acres of Rappahannock river bottom and founded the Rappahannock Oyster Company, harvesting spat (or baby oysters) from public reefs and letting them mature on his property for up to three years.

James continued farming until his death in 1961. At that time, his son Bill took over, growing the company with hundreds of acres of leases. Upon his death in 1991, Bill left the company with nothing more than a few hundred acres of leased river bottom and no one to continue running the operation.

Virginia’s Native Oyster Struggles to Thrive

By 2001, harvests of Chesapeake Bay oysters were down to less than 1 percent of their historic highs because the methods proved unsustainable. Over-harvesting and dredging had destroyed not only the oyster population but also the oyster reefs, where spat attach and grow, and which protect shorelines and fish alike. Virginia’s native oyster, Crassotrea Virginica, was on the brink of being added to the endangered species list. This seemed like the most unlikely time for cousins Ryan and Travis Croxton to take over their great-grandfather’s business, yet they saw it as a great opportunity to carry on the family legacy.

The Virginia oyster harvest was at its lowest in the 70s and 80s, according to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), with harvests of around 20,000 bushels a year. Since then, the CBF has worked to improve water quality and restore oyster populations. After the bountiful harvest of the late 80s, Virginia’s oyster fishery crashed due to overharvesting and disease. Now, the oyster harvest is showing signs of recovery. Virginia Marine Resources Comission is recommending harvesters be conservative when increasing harvest amounts to avoid curtailing long-term recovery.

In 2023, Oyster season was extended by two weeks in March and April in portions of Virginia waterways where the oyster population is high. This was in addition to the season extension Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) approved in January for parts of the James and Rappahannock Rivers.

Sustainable Harvests and Farming Virginia Oysters

“Since our fathers were not in the oyster business, we had a clean slate,” says Ryan. “When we started, we just went online and started searching for aquaculture.” What they found was a method called “off-bottom” aquaculture. By building cages with legs and progressively larger mesh, Ryan and Travis were able to grow full-sized oysters from hatcheries in just three years.

Keeping the oysters off the muddy bay floor also gave them better access to food and water, resulting in a more flavorful product. These are the cages that were being pulled out of the water that cold morning on the Chesapeake Bay.

As we pulled back in to the dock, the peacefulness of the morning on the water changed over to a frenetic energy. The guys unloaded the boat and began emptying the cages into what could best be described as a washing machine—a long cylindrical tube that sprayed the oysters with water as they rotated down onto a conveyor belt. The noise was deafening!

With practiced hands, farm manager Michael Robertson, also known as “Chig,” and his crew set to work cleaning, picking and sorting the oysters, looking for the right shapes and sizes. Rappahannock takes pride in providing its clients with consistent product, so every oyster is sorted by hand. It’s a long, time-intensive process, but Ryan and Travis believe that aquaculture is one of the keys to revitalizing Virginia’s oyster industry. “Our goal is to take the pressure off of the wild population so that it can rebound,” Travis said. By farming in cages that sit above the bay floor, the oysters are able to provide the ecosystem of the bay with environmental benefits without disturbing the natural growth they all are working towards. Oysters are a keystone species that provide habitat for fish, crabs and worms. Filter feeding oysters remove light-blocking algae from the water and remove excess nutrients. This improves the overall water quality.

Watching Chig, it was clear that oyster revitalization is a big part of their “corporate culture.” And as we sampled oysters right off of the conveyor belt, just minutes out of the water rom their oyster farm, I had to admit that this is the sort of corporate culture I can get behind.

Rappahannock Oyster Co Works to Save the Virginia Oyster

It’s expected that not every oyster would make the cut that morning. One was not round enough, another not quite large enough and another had too much damage to the shell. Each of these oysters would benefit from another three to six months out in the water, so they are tossed into a basket and taken back out to the bay, not wasted. Based on client needs, the oysters can also be moved to one of Rappahannock Oyster’s multiple locations to take on their distinctive flavors.

Travis is happy to cooperate with the Virginia Marine Resources Commission as they set limits on harvesting from public oyster grounds and limit the practice of dredging so that we can see continued growth of our native Virginia oyster. This goal is what makes Rappahannock Oysters so unique.

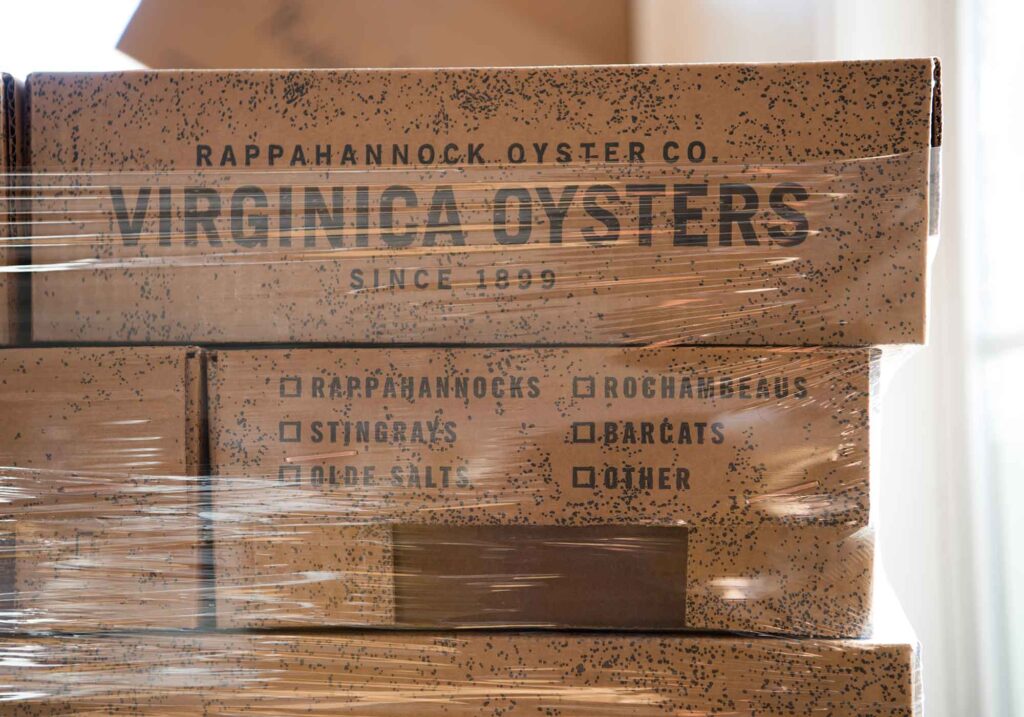

Director of Farms Patrick Oliver makes it clear. “With people taking over the land, we’ve got to get aquaculture right. It’s going that direction.” Getting it right includes supporting others who are looking to get it right. By forming a co-op product know as Barcat Oysters, Rappahannock Oysters supports small-time oyster farms and former “wild” harvesters from all across the Chesapeake Bay, helping to make sure locations can take on their distinctive flavors.

“We’re in a good place now,” says the CBF spokesperson. But we still have to remember that oysters are still a fraction of what they were historical.” The balance between harvesting oysters and ensuring there are enough in the water is vital to the health of the Bay. This will ensure that populations remain stable in the face of environmental stressors like disease or major weather events.

Tasting and Pairing Oysters in Virginia Wine Country

The changes in flavor from oyster to oyster are due to the fact that they are filter-feeders, sucking in the available water, plankton and algae, and taking on the properties of their environment. The team refers to this as “merroir,” a play on the French word for “sea” (mer) and the French word for “land” (terroir), used to describe the characteristic flavor imparted to wine by the environment in which it is produced. By filtering the water and reducing risks of algae blooms, oysters play an important role in cleaning up the Bay, restoring oxygen levels that allow other sea life to thrive. It’s also the reason that Chief Operations Officer Anthony Marchetti believes oysters are a vital and sustainable protein source moving forward.

In 2015, Governor Terry McAuliffe appointed Anthony to be a part of his Aquaculture Advisory Board. It was their belief that aquaculture was key to revitalizing Virginia’s oyster industry. “Our goal is to these individuals focus on quality, sustainability and environmental stewardship,” the same ideals that they believe will restore the Virginia oyster industry.

Over the past 10 years, Rappahannock Oysters has grown from harvesting 10,000 oysters a week to over 180,000 oysters each week, all while maintaining its commitment to help restore the wild Virginia oyster population and to clean up the Chesapeake Bay. They use practices from all over the world, information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and a lot of research to produce the best, most sustainable product.

And what better way to enjoy such fresh cuisine than with amazing wine. A wine with light, crisp acidity allows the oyster to shine. When eating Virginia oysters though, it seems only fitting to pair them with a Virginia beverage. Wine expert Richard Leahy advises pairing a dry sparkling wine with raw oysters to balance the saltiness of the merroir. Chardonnays often work well with cooked and seasoned oysters. Reading Leahy’s complete guide to pairing wine and oysters will give you detailed information for the perfect pairing. For more on Virginia’s wine movement and oyster connoisseur himself, Thomas Jefferson, read our overview of Virginia’s Great American Wine Story. If you’re looking for inspiration on other farm-to-table experiences, check out this story on Pippin Hill Vineyard’s unique dining experience. ~

BRIAN MELLOTT has a master’s degree in education, and is a writer and photographer whose work shows his passion for food and the people who create it.

R. L. JOHNSON is our Co-Publisher and Creative Director. Bethke studied at the prestigious ArtCenter College of Design and began her career as a professional photographer in Los Angeles. She moved into graphic design and art direction when she relocated to Charlottesville in 1994. As our company’s co-founder and visionary, she enjoys all aspects of storytelling.